It was a campfire tradition from my Boy Scout days that inspired me to get into podcasting. I loved sitting around a campfire with my friends at the end of the day to share a meal and tell stories. This component of humanity might be one of the oldest traditions to date. Before phones and the internet, news and information was passed from person to person around a warm fire somewhere along the trail. Communication methods and mediums may have changed over the last 12,000-ish years of human history, but the tradition of storytelling remains the same. This part-time project of mine, The Tennessee Ghosts and Legends podcast, is one small way to keep that storytelling tradition alive.

You can listen to this episode here.

Before we begin the stories in today’s episode, let’s first look at the Native American landscape of Tennessee during the westward expansion.

The first days of the territory now known as Tennessee as settlers moved west saw two primary tribes across the state: the Chickasaw and the Cherokee. Prior to their arrival, the major tribes were the Yuchi, the Shawnee, and the Muscogee, among other smaller bands. When the first white settlers arrived, their early push into Tennessee started with the Cherokee in the east. Most of the legends you’ll hear today are from books on the Cherokee traditions and are not all inclusive of the many rich stories of native culture. I highly recommend further reading for a deeper understanding of how these fascinating tales came to be.

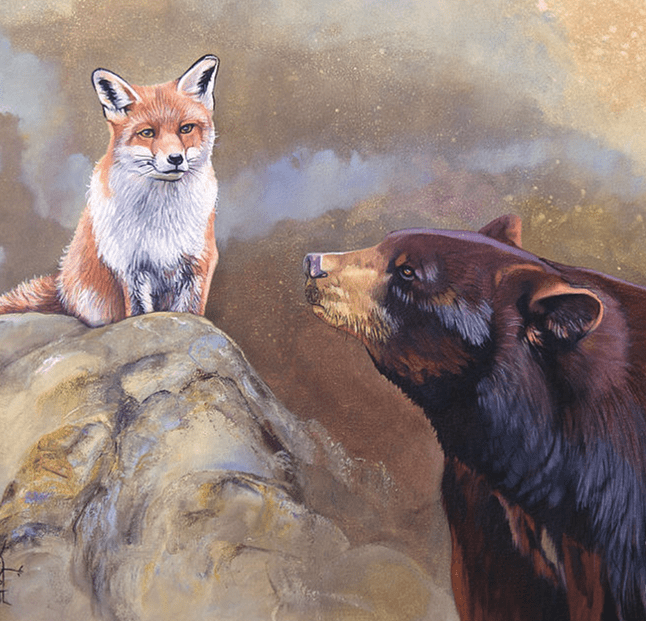

Why Black Bears do not have Tails

Our first story is from a Cherokee tale about why Black Bears, which are revered in Cherokee culture as spirit guides, do not have a tail like many other forest-dwelling mammals. Harvesting a Black Bear is viewed by the Cherokee with great ceremony and reverence. The bear provided food with his meat, clothing and bedding with his hide, lamp oil from his winter stores of fat, and tools from his bone. Robes made from Black Bears are worn by Cherokee warriors and hunters paying homage to the courage and ferocity of the bear. These legends surrounding bears were shared with children and bedtime stories. At some point, one of them must have asked why bears do not have tails. The fault for this was blamed on the wily fox.

The fox is viewed in many cultures as a sly trickster who likes to outsmart humans and other animals. In this legend, it is said that after an abundant harvest season in the Great Smoky Mountains, the weather was turning cold, and it was time for the Black Bear to find his den for the winter. At this time, Black Bears had long and luxurious tails that they were quite proud of. Their tails were so beautiful that it is said the fox was jealous of it. On a cold early morning while roaming the creek sides searching for fish to eat for his winter fat stores, the Black Bear happened upon a fox sitting on a chuck of ice with his tail hanging down into the cold water. The bear asked the fox what he was out so early by the creek.

“To catch fish, of course,” the fox replied. “I am going take my catch to the village and trade it for a tortoise shell comb for my tail. With a comb, my tail will be the most beautiful tail in the forest.” The fox knew making such a claim would anger the proud black bear, so he added more insult to his boast. “I know I’ll have plenty of fish to trade because the whole forest knows I am the best fisherman in the woods—even better than you, bear.”

“Ha!” said the bear, taking the proverbial bait. “You can’t catch more fish than me, and my tail is more beautiful than yours. You think you’re so smart. If I fish all day and night, I’ll catch way more fish than you.”

“Try it then, bear,” challenged the fox. “Let’s see whose tail can attract the most fish!”

So, the Black Bear found another chuck of ice and put his long tail into the water. They both had success pulling up may trout, but the bear could not let the fox win. He sat on his ice chunk well into the night. As the darkness and cold set in, the bear became sleepy and was soon in a slumber. Seeing this, the fox pulled his frozen tail from the water and went to his warm den nearby to wait. Overnight, the water froze around the bear’s tail. In the morning, the bear woke to find himself stuck in the ice. The fox came back and saw what happened. The bear was distraught.

“I can’t get out of the ice. Help me, fox!” the bear cried. The fox, feeling sorry for tricking the bear into doing this challenge, agreed to help. The fox ran as fast as he could across the rocks to try and knock the bear out of the ice. After several tries, the bear finally got out, only to find he got out without his tail that remained stuck in the ice. The bear began to wail in anguish over the loss of his tail. The fox, seeing how upset the bear was after this awful prank, vowed to the bear he would be his best companion forever.

While this tale is obviously a colloquial fantasy story, there are some natural remnants of truth. While many woodland creatures are afraid of the mighty Black Bear, and for good reason, it is common to find a fox nearby who scavenges from the leftovers of a bear’s kill. They are sometimes even seen feeding from the same carcass. This symbiotic relationship works both ways by creating a landscape of fear to other predators who may stalk the fox, like coyotes or bobcats. They dare not approach a fox if a bear is nearby. It is possible that this coexistent relationship was seen by native hunters and passed on to families who craved tales from a hunting party and what they saw. Those tales may very well have forged the story of why a black bear doesn’t have a tail.

Reelfoot Lake

Our next legend comes from the far northwest corner of Tennessee and speculates about the true formation of Reelfoot Lake. The scientific explanation is this: The lake was formed by an earthquake along the New Madrid fault between Tennessee and Arkansas in 1811, causing the Mississippi River to flow backwards for a short time. The change in waterflow back flooded the low-lying area that was called Reel Foot River. That 40,000-acre cypress swamp held all that water and is now a state park called Reel Foot Lake. A Chickasaw tradition gives a similar, yet quite different reason for the formation of the lake.

Around 1790, a Chickasaw chief in that area had a son born with a deformed foot. As the child grew, the deformity evolved and caused him to walk with a noticeable reeling gait. Henceforth, he was called Kalopin, which roughly translates to Reelfoot. After the death of his father around 1810, Reelfoot became chief of his tribe and was unmarried. Many of the maidens in his camp mocked his deformity and would not marry him. However, it was unheard of to have a chief with no wife, so Reelfoot took a party of his most trusted warriors south into Cherokee lands to look for a bride.

Before long, they found the camp of a chief named Copiah. In the two versions I found of this tale, it is unclear if Copiah was a Chocktaw or a Cherokee chief, and in another version, he is called Copish. These anomalies are common among spoken word tales. In any case, the two chiefs shared a meal in friendship where Reelfoot revealed why he had come. Chief Copiah understood Reelfoot’s plight, stating that the only eligible maiden of-age in his camp was his daughter, a beautiful young princess named Laughing Eyes. Reelfoot immediately fell for her beauty and begged Copiah to allow him to marry her. However, Copiah refused and would not allow his daughter to be wed to a chief with a deformity. Their discussion continued long into the night. Reelfoot offered many bundles of beaver skins and deer hide bags of mussel pearls for her hand, yet Copiah refused. After begging nearly to the point of embarrassment, Copiah became angry with Reelfoot and made him leave the camp, never to return.

Reelfoot was angry and felt humiliated by his treatment. One version said he was forcefully removed from the camp at spear-point. However, that did not sate his desire to marry Laughing Eyes. He rallied his warriors to a hidden bluff nearby and waited for days until Copiah let his guard down.

The night before the planned raid, Reelfoot had a dream. The Great Spirit showed him a vision of a great calamity upon them should Laughing Eyes marry outside of her tribe. He saw the destruction of both camps under a great upheaval of the land. In the morning, he shared his dream with one of his wisest warriors who warned Reelfoot to abandon the idea of going back to steal Laughing Eyes. He told him the vision was a bad omen, and that no good would come of raiding his camp for her. The other warriors agreed and begged him to reconsider this plan. Still, Reelfoot would not be swayed. That night was cloudy and moonless, so Reelfoot decided to proceed. He and a few select warriors snuck into Copiah’s camp after everyone was asleep and kidnapped Laughing Eyes, stealing her away without a sound.

Back at his camp, Reelfoot sent some warriors ahead to prepare the village for the wedding, warning them not to mention his vision about destruction upon the land, and he admonished his wise brave for causing alarm along the party.

When Reelfoot and Laughing Eyes arrived at the crossing for Reel Foot River, a tribal boundary between his lands and Copiah’s, a loud sound enveloped them unlike anything they had ever heard. In his pride, he thought it was the welcoming sound of drums as he rode triumphantly into his village with his stolen bride. However, the ground beneath them began to shake and a great chasm opened across the river. Trees fell all around them in mighty cracks and heaves. Then, a tremendous wall of water rushed through the marsh, engulfing them all beneath the waves and burying them at the bottom of the newly formed lake. It is said that visitors to the lake claim to hear the sound of pounding drums, and I found one unconfirmed report of a camper by the lake claiming a strange ran through his campsite with a pronounced limping gait like he was running from something terrifying, though no trace of him was ever found.

The Legend of Spearfinger

Our next story takes a darker turn and explores a Cherokee legend about a shapeshifter known as U’tlunta, or Spearfinger. This creature is said to haunt the mountainous Appalachian borderlands between North Carolina and Tennessee. U’tlunta gets her name from her supernaturally long forefinger which is a blade made from obsidian. She roams from village to village, changing her appearance to gain entry, then coaxes children to an isolated place where she kills them and eats their liver. The tales say her natural appearance is pale grey and ghoulish with bright red staining around her mouth and neck from the blood of her victims, and that she is possibly made of stone from the mountain.

Her usual tactic was to locate Cherokee villages by following the smell of campfire smoke, or by the smoke of the autumn brush burnings Cherokee villages would do to manage brush fire risks nearby. Once she finds a village, she takes the form of a kind old woman with thick robes to hide her long obsidian-bladed finger. After getting in, she would befriend the children of village, especially the little girls, by offering to brush their hair and make them beautiful for the warriors. Once she had a target, she would puncture the back of their necks with her finger to paralyze them. After a few days when the child died, she would sneak into their tents, open their bellies, and eat the liver. It is said once she consumed the liver, she could then hide the body and take on the shape of her victim. The miraculous recovery would allow her easy access to the rest of the family, which she would also kill one by one and eat their livers.

This is one of the few tales about a murderous creature that also comes with instructions on how to destroy her. The legend says the only way to kill Spearfinger is by stabbing her through the heart, which she kept in her clenched fist. The legend states that one Cherokee village took action after losing multiple families to the creature. Once they identified who she was, the dug a large pit near one of the camps she stalked and filled the bottom with sharpened spikes. They then covered the top with brush and started a large campfire nearby. The villagers roasted chestnuts to sweeten the temptation for Spearfinger.

The creature took the bait, appearing as an old woman asking for entry to the camp to join the celebration. A group of warriors emerged from a nearby tent with bows drawn, firing arrow after arrow with no effect against her stony hide. Enraged, she appeared in her natural form with sharp teeth bared from her bloody face. She charged the warriors and fell into the pit. As the warriors fired more arrows down at the writhing creature, it is said a tufted titmouse landed in the tree above them, crying, “heart, heart, heart!” The braves fired arrows at her chest with no effect when a chickadee flew down and landed on Spearfinger’s clenched hand. Understanding the sign, a warrior threw a spear at her hand, hitting her wrist and causing her to drop her heart. Another warrior’s last arrow rang true, piercing the dislocated organ and ridding the Cherokee of Spearfinger’s menace forever.

This story was hard to find as a whole. I dug through several books and watched videos for snippets but could not find a full telling of this story. In my research, I could not help but notice the parallels of Spearfinger and of Eastern European vampire lore. I cannot help but wonder if perhaps a merging of cultures from Native Americans and Europeans moving westward created this blended macabre tale.

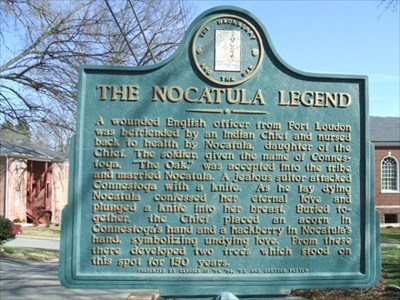

The Legend of Nocatula and Connestoga

Our last tale for this Thanksgiving episode is not as dark, but more of a tragic romance. The Legend of Nocatula is fairly well-known around the area of Tennessee Wesleyan University in Athens, Tennessee and is one of only a few Native American legends where there was physical evidence.

This story begins in 1756 at Fort Loudon in Loudon, Tennessee, which is in Loudon County just south of modern-day Knoxville. At the time, Fort Loudon was the furthest western outpost built by the British during the colonial period to ward off the French coming north from their ports on the Gulf of Mexico. The British were allied at the time with the Overhill Cherokee in that area. A mutual understanding was made surrounding the fort’s construction. It was not built out of aggression but out of protection. The gates were open to British colonists and Overhill Cherokee alike. When the fort was completed, a friendship was born between the fort’s designer, James William Gerald deBrahm, and a Cherokee named Attakulla-Kulla. deBrahm had a penchant for sideshow magic as well, and shared his knowledge of building and alchemy with the young Cherokee. Attakulla-Kulla was also a conjurer of sorts among the Cherokee and taught deBrahms some of the more mystic ways of the Cherokee. This respectful bond of friendship would become critical to our story only four years later.

As more settlers came westward, many of the new arrivals did not share the same respect for the Cherokee as the original builders of the fort did. In their settlements outside the fort, many of the new settlers clashed violently with the indigenous In February of 1760, the relationship ended violently with an Indian attack on the fort to oust the settlers. The fort outlasted the siege for almost six months before finally surrendering under starvation and illness. Supplies had run out. All of the animals, included horses and dogs, were slaughtered for food out of desperation. In late August, the Cherokee took the fort.

The surrender agreement was to provision those who remained with food and grant safe passage back to Fort Prince George in South Carolina (which was ironically also attacked by the Cherokee in 1760 but did not fall) near modern-day Pickens County in South Carolina. After the first day of the trek to South Carolina, the bedraggled settlers stopped to camp at Cane Creek about 15 miles east of Fort Loudon. The following morning, a war party laid siege to the refugees, slaughtering thirty people. Among the survivors was a woman with a young child who begged for her life after her husband was slain in the raid. Showing a hint of recognition of her during his days spent with deBrahams, the Indian who was now called Chief Attakulla-Kulla claimed the woman and child as his prisoners. The rest were taken prisoner by the Cherokee and are lost to history.

Chief Attakulla-Kulla treated the woman and child kindly, and she eventually became his wife. Little is known about what happened to the child that survived the massacre, but they had another child later, a girl they named Nocatula. As with most stories with these elements, Nocatula grew to be the most beautiful maiden among the Overhill Cherokee, and by rights as a natural-born child of Attakulla-Kulla, his heir. The warrior who married her would become the next chief, and many would try. One warrior in particular, known as Mocking Crow, was seen as the obvious choice.

The problem was, Nocatula hated Mocking Crow. She thought him boastful, prideful, and unnecessarily cruel. That did not stop him from trying. He brought gifts to Attakulla-Kulla for her hand. He showed his prowess in battle and as a hunter and provider. He boasted of a strong family with deep roots in the tribe. Most of all, he bragged publicly about how she would eventually relent, and Nocatula would be his. For this, she despised him.

By this time, the American Revolution against England was in full swing. Attakulla-Kulla’s band of Overhill Cherokee largely stayed out of the conflict, but occasionally they would cross paths with the aftermath of battles near the border of Tennessee and the Carolinas. One such incident happened in early October of 1780 after the infamous Battle of Kings Mountain. Attakulla-Kulla’s hunting party came upon a badly-wounded British soldier lying in the woods. He had crawled away from the melee to avoid capture when the Americans turned the tide of that battle and thought he would die there. Having a soft heart for white settlers that stemmed from his early friendship with deBrahms, Attakulla-Kulla ordered his hunters to build a litter and carry him back to their village.

When the men arrived with the soldier, Chief Attakulla-Kulla put him under the care of Nocatula and ordered his protection. Some of the warriors did not like having a white man among them, however the chief would not allow any harm to come to him. Over the next few months, Nocatula nursed the young soldier back to health. In the time they spent together, they fell in love.

The day came when the soldier regained his former strength, yet found he had nowhere to go. He could not go back to the British army where he would be branded a deserter, and many of the warriors did not want him among them unless he was part of the tribe. One of his fiercest critics was none other than Mocking Crow, demanding he be cast out and never return. Attakulla-Kulla had seen the budding romance between his daughter and the soldier during his healing process, and he knew that the man made his daughter happy. He decided that the two would marry and gave him the tribal name of Connestoga, meaning “The Oak” in Cherokee. Conestoga and Nocatula would soon marry and he was accepted as one of the tribe by all except for, of course, Mocking Crow.

As part of Connestoga’s initiation into the tribe, he would have to learn to hunt like a Cherokee. Soon, a morning came where a great hunt was declared, and Connestoga would be among the lead party. He was excited and nervous, but eager to prove himself worthy of the prestige Attakulla-Kulla had bestowed upon him. He bid his new bride Nocatula a tearful goodbye and marched into the woods with a new life ahead of him.

They had not gone far into the woods before coming upon a small herd of deer. The party took positions and showed Connestoga how to stalk them silently. He stayed to the center while his companions moved to flank the herd. Just before his companions gave the signal to move, a rustle of leaves behind him caused him to turn just in time to see Mocking Crow burst from the brush and drive his hunting knife deep into Connestoga’s neck. While he was distracted stalking the deer, he had no idea that he, himself, was the actual prey.

Hearing the commotion brought his companions running back, but they were too late to catch Mocking Crow. They sent the fastest of the party back to the village for help and to bring Nocatula with medicine. When she arrived, Connestoga was still alive, but barely. She sobbed over his pale body. He had lost so much blood and his breathing was shallow. She tried to wipe the blood off of his face, crying that she could not live without him and begging him to live. He finally drew his last breath and went limp in her arms. She cried out in anguish when he died. Next to him lay the weapon, a knife she recognized as belonging to Mocking Crow. She knew why he did this, and she would deny him a final time. She picked up the knife and drove it deep into her chest. Her aim was true, and she fell dead next to Connestoga in an instant.

Moments after, Chief Attakulla-Kulla arrived to find his daughter lying dead next to the soldier he took on as his own son. He remained stoic, reciting the age-old prayers as was the custom of the Cherokee, and offered a lament for the dead. He whispered a command to a nearby warrior to ran off into the brush. As the others stepped forward to prepare the bodies, the chief spoke.

“No,” he said. “They will not be moved from here, from the place that they have died. They will be buried here.” The warrior who ran off returned a few moments later, handing Attakulla-Kulla two acorns; one a White Oak and one a Hackberry Elm. He placed the oak acorn in Connestoga’s clenched hand and the other in Nocatula’s. The party buried them in the same place with the earth that was soaked with their own blood, spilled in jealousy but bound for eternity.

The two trees grew. For 165 years, the oak and the hackberry stood tall and straight, side-by-side. Tennessee Wesleyan University in Athens, Tennessee was built on this very site in 1857. The legend of Connestoga and Nocatula was known, and the trees were left undisturbed during the construction. Sadly, the trees are longer with us. In 1945, the hackberry showed signs of disease and decline and had to be removed. The white oak, losing its companion tree, also showed signs of disease and decline a short five years later and was removed. What remains today is a historical plaque on the TWU campus along Coach Dwain Farmer Drive, standing on the site where the two doomed lovers died and two living monuments stood in their place for over a century thereafter.

In the twenty episodes I have recorded so far, this is one of my favorites. Legends like these are rich in history and reflect a minimal time in life where the disappearing art of story-telling took precedence over the rush of modern day life and technology. One of the greatest sources of stories like these is not necessarily from books, but from people. If you have an elderly person in your life, talk to them. Hear their stories, not as a book says it or the internet says it, but as they say it. After you hear these stories, I challenge you to pass them on. Keep the art of story-telling alive and well. You never know what will grow from your legend.

Thank you for listening to today’s Tennessee Ghosts and Legends Podcast episode. I am certain that my pronunciation of many of the native American names in this episode are spoken incorrectly. I appreciate your grace and forgiveness on my lack of linguistic understanding of indigenous speech. If you’d like to read more about this and other stories I’m working on, I cordially invite you to visit my website at www.lylerussell.net. I am your host, Lyle Russell, and remember, the dead may seem scary, but it’s the living you should be wary of. Happy Thanksgiving. Until next time.

Leave a comment